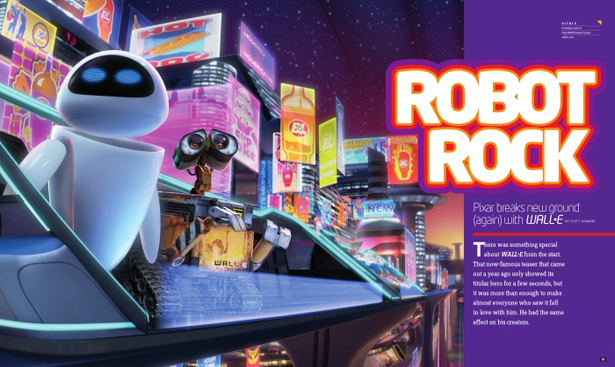

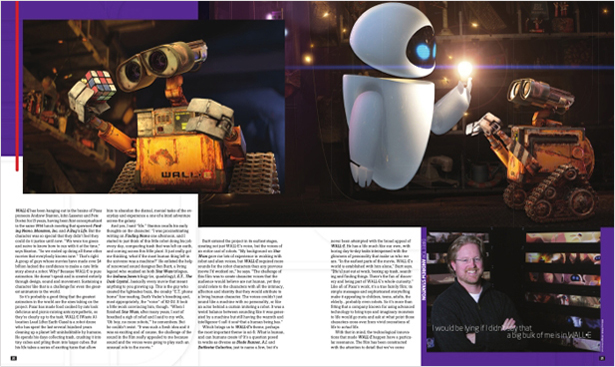

Robot Rock Pixar breaks new ground (again) with WALL•E There was something special about WALL•E from the start. That now-famous teaser that came out a year ago only showed its titular hero for a few seconds, but it was more than enough to make almost everyone who saw it fall in love with him. He had the same effect on his creators. WALL•E has been hanging out in the brains of Pixar pioneers Andrew Stanton, John Lasseter and Pete Docter for 15 years, having been first conceptualized in the same 1994 lunch meeting that spawned Finding Nemo, Monsters, Inc. and A Bug’s Life. But the character was so special that they didn’t feel they could do it justice until now. “We were too green and naive to know how to run with it at the time,” says Stanton. “So we ended up doing all these other movies that everybody knows now.” That’s right: A group of guys whose movies have made over $4 billion lacked the confidence to make a cute little story about a robot. Why? Because WALL•E is pure animation. He doesn’t speak dialogue and is created entirely through design, sound and movement. Sustaining a character like that is a challenge for even the greatest animators in the world. So it’s probably a good thing that the greatest animators in the world are the ones taking on the project. Pixar has made food cooked by rats look delicious and picnic-ruining ants sympathetic, so they’re clearly up to the task. WALL•E (Waste Allocation Load Lifter Earth-Class) is a robot drone who has spent the last several hundred years cleaning up a planet left uninhabitable by humans. He spends his days collecting trash, crushing it into tiny cubes and piling them into larger cubes. But his life takes a series of exciting turns that allow him to abandon the dismal, menial tasks of the everyday and experience a one-of-a-kind adventure across the galaxy. And yes, I said “life.” Stanton recalls his early thoughts on the character: “I was procrastinating writing on Finding Nemo one afternoon, and I started to just think of this little robot doing his job every day, compacting trash that was left on earth, and coming across this little plant. It just really got me thinking, what if the most human thing left in the universe was a machine?” He enlisted the help of legendary sound designer Ben Burtt, a living legend who created the sound design for both Star Wars trilogies, the Indiana Jones trilogy (er, quadrilogy), E.T., The Dark Crystal…basically every movie that meant anything to you growing up. This is the guy who created the lightsaber buzz, the croaky “E.T. phone home” line-reading, Darth Vader’s breathing and, most appropriately, the “voice” of R2-D2. It took a little work convincing him, though. “When I finished Star Wars, after many years, I sort of breathed a sigh of relief and I said to my wife, ‘oh boy, no more robots,’” he remembers. But he couldn’t resist. “It was such a fresh idea and it was so exciting and of course, the challenge of the sound in the film really appealed to me because sound and the voices were going to play such an unusual role in the movie.” Burtt entered the project in its earliest stages, creating not just WALL•E’s voice, but the voices of an entire cast of robots. “My background on Star Wars gave me lots of experience in working with robot and alien voices, but WALL•E required more sounds for the robot characters than any previous movie I’d worked on,” he says. “The challenge of this film was to create character voices that the audience would believe are not human, yet they could relate to the characters with all the intimacy, affection and identity that they’d attribute to a living human character. The voices couldn’t just sound like a machine with no personality, or like an actor behind a curtain imitating a robot. It was a weird balance between sounding like it was generated by a machine but still having the warmth and intelligence–I call it soul–that a human being has.” With that in mind, the technological innovations that made WALL•E happen have a particular resonance. The film has been constructed with the attention to detail that we’ve come to expect from a Pixar production. “WALL•E is a sort of all-purpose base robot model,” explains Stanton. “I always kind of equate him to a tractor.” To that end, animators extensively studied heavy machinery such as giant crushers at recycling facilities to get a feel for their mechanics. They paid special attention to a device called a tank chair, which is a sort of off-road wheelchair that can greatly improve the mobility of the disabled. “It had little tank treads on it and could kind of go all over hill and bale. We were fascinated to see how that worked, because we were thinking of WALL•E being designed in a similar fashion—able to go over all terrain.” They also delved into the world of sci-fi and silent cinema to learn the visual language of genres that were new to them. Production designer Ralph Eggleston (The Incredibles, Finding Nemo) based the look on ‘60s and ‘70s NASA paintings and original concept paintings for Disneyland’s Tomorrowland, which are delightfully retro-futuristic today but were an honest attempt at glimpsing ahead at the time. “Our approach to the look of this film wasn’t about what the future is going to be like; it was about what the future could be, which is a lot more interesting,” he says. “We want the characters and the world to be real, not realistic looking, but real in terms of believability.” The idea of a believable unreality extended to the film’s photography. Few think of cinematography on an animated film, but the noir complexity of The Incredibles and the warm Parisian skylines of Ratatouille were a major part of those films’ success, and a similarly distinctive palette was developed here according to Jeremy Lasky, director of photography. “The whole look of WALL•E is different from anything that’s been done in animation before. We really keyed into some of the quintessential sci-fi films from the ‘60s and ‘70s as touchstones for how the film should feel and look.” And their considerations don’t end there. Cinematic attention to detail is what sets Pixar’s work apart, and they even try to replicate cameras. “We used a widescreen aspect ratio and a very shallow depth of field to give a real richness to the cinematography,” Lasky continues. “We also used a lot of handheld and steady-cam shots, especially in space, to make the audience feel that could really happen, and that this is a real robot moving through a real world.” It’s an astounding effort, and one that proved to be even more complex than Andrew Stanton originally thought. “When you’re a writer/director on a film, it’s all on you to either come up with the idea for something, or the direction of something, or to instigate it from somebody. And there was a lot to do on this film, particularly in comparison to what it was like on Finding Nemo. I thought Nemo was really hard, but I now look back at how much of a start we had by already working with an ocean, and creatures that pre-exist, and aquariums in dentists’ offices.” But creating an entire world from scratch is quite a different story. “You have to spend more time just coming up with possible logical answers, and then on top of that come up with interesting, fancy, cool ways to show it. Those are two completely time-consuming things to do, so it was double the work on this than what I expected.” But his efforts are far from in vain. Pixar sets the bar higher and higher with each and every outing, but WALL•E may be their best yet: a heartfelt and awe-inspiring modern classic that will entertain audiences for decades to come.

Pixar usually stays silent about their upcoming projects until they’re close to completion, but their slate for the next four years was announced as part of Disney’s spring presentation to stockholders. There are a few sequels, a few new collaborators and a whole lot of 3D (all are being prepped for Disney Digital 3D). Just go ahead and clear your schedule for Christmas 2011. Up Toy Story 3 newt The Bear and the Bow Cars 2 |

| © copyright scott howard |

July 2008

July 2008 Which brings us to WALL•E’s theme, perhaps the most important theme in sci-fi: What is human, and can humans create it? It’s a question posed in works as diverse as Blade Runner, A.I. and Battlestar Galactica, just to name a few, but it’s never been attempted with the broad appeal of WALL•E. He has a life much like our own, with boring day-to-day tasks interspersed with the glimmers of personality that make us who we are. “In the earliest parts of the movie, WALL•E’s world is established with him alone,” Burtt says. “[He’s] just out at work, boxing up trash, searching and finding things. There’s the fun of discovery and being part of WALL•E’s whole curiosity.” Like all of Pixar’s work, it’s a true family film; its simple messages and sophisticated storytelling make it appealing to children, teens, adults, the elderly...probably even robots. So it’s more than fitting that a company known for using advanced technology to bring toys and imaginary monsters to life would go meta and ask at what point those characters cross from vivid recreations of life to actual life.

Which brings us to WALL•E’s theme, perhaps the most important theme in sci-fi: What is human, and can humans create it? It’s a question posed in works as diverse as Blade Runner, A.I. and Battlestar Galactica, just to name a few, but it’s never been attempted with the broad appeal of WALL•E. He has a life much like our own, with boring day-to-day tasks interspersed with the glimmers of personality that make us who we are. “In the earliest parts of the movie, WALL•E’s world is established with him alone,” Burtt says. “[He’s] just out at work, boxing up trash, searching and finding things. There’s the fun of discovery and being part of WALL•E’s whole curiosity.” Like all of Pixar’s work, it’s a true family film; its simple messages and sophisticated storytelling make it appealing to children, teens, adults, the elderly...probably even robots. So it’s more than fitting that a company known for using advanced technology to bring toys and imaginary monsters to life would go meta and ask at what point those characters cross from vivid recreations of life to actual life. Planning Ahead

Planning Ahead